Timeline: LBJ and the Nation

1908-1919 1920-1929 1929-1940 1941-1945 1946-1953 1954-1960 1960-1963 1963-1969 1969-1973

1963-1969

In his first Inaugural Address, President Johnson declared a national War on Poverty. For the weapons to fight that war, he proposed an array of government programs. One of the first arenas of action for his administration was the historic 1964 Civil Rights Act, landmark legislation that ended legal discrimination in the United States.

Initiatives of the Johnson administration moved the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. closer toward a normalization of relations than at any time since the end of World War II. "Our plan to place a man on the moon in this decade remains unchanged," the president pledged at the beginning of his administration. Johnson also pledged to continue Kennedy's Vietnam policy that gradually culminated in the war that broke America's will.

“Nineteen sixty-eight,” President Johnson wrote after leaving office, “was one of the most agonizing years any president ever spent in the White House. I sometimes felt that I was living in a continuous nightmare.”

Thrust by tragedy into the glare of public attention, Lady Bird Johnson said, “I feel as if I am suddenly on stage for a role I never rehearsed.” Asked what image she hoped to project, she responded: “My image will emerge in actions, not words.”

Events

The 1964 Campaign

Seeking to win the presidency in his own right, Lyndon Johnson asked for a mandate from the voters to create a "Great Society," which he envisioned as a range of social programs that would improve the quality of life for the American people. His opponent was Barry Goldwater, unofficially titled "Mr. Conservative" because of his political and social philosophy. The election was a landslide victory for Johnson and Inauguration Day 1965 promised to be the beginning of a new and golden age in the life of the nation.

The Great Society

Activist, pragmatist, optimist—Johnson was all three. “We have the power,” he told students at the University of Michigan in 1964, in the speech that launched the Great Society, “to shape the civilization we want.’ The philosophy under girding the Great Society was that old injustices could be eliminated and the quality of life improved for everybody. Johnson believed that the resources of government could be, and should be, mobilized for the betterment of the people.

It was the greatest outpouring of legislation in America’s history: laws to end discrimination and to fight poverty; to provide medical care to the old and extend educational opportunities to the young; to clean the air and water and reverse the pollution of decades; to preserve precious land for public recreation and to protect the natural beauty of the continent; to bring art and music and theater to every corner of the nation; to protect the consumer in the marketplace.

The Thousand Laws of the Great Society LBJ and the World

Initiatives of the Johnson administration moved the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. closer toward a normalization of relations than at any time since the end of World War II. Other foreign policy measures included programs to encourage Third World countries to form common markets and regional partnerships; the first effort to build bridges to the nations of Eastern Europe; a change in policy toward India that staved off a famine that threatened millions; preservation of the NATO alliance at a critical time; and stabilization of the international monetary system.

The “Hot Line” was a pair of teletype machines, one in Washington, the other in Moscow, that use and the Kremlin in an emergency. It was used for the first time in the Six-Day War between Israel and its neighboring Arab states in 1967. Johnson and Soviet leader Aleksei Kosygin used the hot line initially to exchange assurances that each would exert his influence to try to end the fighting.

But in the public’s mind, and increasingly to the frustrated president, all were overshadowed by the dominant struggle of the day. Vietnam is about two-thirds of what we talk about these days. Lady Bird Johnson, A White House Diary.

The Six-Day War

The conflict began when Egypt closed the Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli shipping, violating a decade-old agreement. The U.S. attempted to find a way out of the problem through diplomatic efforts, and prepared to join other nations in an armada to accompany Israeli ships through the straits if diplomacy failed. But Israel forced the issue by moving alone to open the passage.

The major danger posed by the war was the possibility of confrontation between the U.S., committed to preserving the integrity of Israel, and the Soviet Union, on whom many of the Arab states had grown dependent. A few days later, Israeli forces opened the Gulf, moved across the Sinai, and captured the Old City of Jerusalem from Jordan.

The Six-Day War ended with a cease-fire. But the tensions between Israel and her neighbors continued into the next generation.

The Path to the Moon

“Our plan to place a man on the moon in this decade remains unchanged,” the president pledged at the beginning of his administration.

And through the following years, astronauts climbed step by step toward that goal, orbiting the earth in two- and three-man missions; walking, working, and rendezvousing in space. Astronaut Edward H. White II became the first American to “walk” in space as he maneuvered outside his Gemini-Titan 4 spacecraft on June 3, 1965. The death of Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee in 1967, in a fire that destroyed their test capsule, threatened the progress of the space program. But momentum was regained, and before the Johnson administration ended, Frank Borman, James Lovell, and William Anders made the first orbit around the moon at Christmas time 1968.

The landing on the moon—the triumphant pay-off of a decade of commitment—took place after Lyndon Johnson left office, on July 20, 1969.

Sen. Lyndon B. Johnson posing for camera with a group of U.S. astronauts and other men

Sen. Lyndon B. Johnson posing for camera with a group of U.S. astronauts and other mencredit: Frank Muto

American Astronauts: Heroes of Space, 1964-1968:

- Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr.

- Donn F. Eisele

- William A. Anders

- Richard F. Gordon

- Neil A. Armstrong

- Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom

- Frank Borman

- James A. Lovell, Jr.

- Eugene Cernan

- James A. McDivitt

- Roger Chaffee

- Walter M. Schirra, Jr.

- Michael Collins

- David R. Scott

- Charles "Pete" Conrad, Jr.

- Thomas P. Stafford

- L. Gordon Cooper, Jr.

- Edward H. White II

- R. Walter Cunningham

- John W. Young

The Vietnam War

In far-off Vietnam, divided since 1954, trouble had simmered for a decade. Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy had supplied economic and military assistance to South Vietnam, to help it develop and to enable it to defend itself against a takeover by communist North Vietnam. In the early 1960s under President Kennedy, American support had grown to include 16,000 military advisers. President Johnson pledged to continue Kennedy’s Vietnam policy.

A new phase in the war opened with the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution (more properly, the Southeast Asia Resolution) in response to reported North Vietnamese attacks on U.S. vessels Maddox and Turner Joy on August 2 and 4, 1964. By early 1965, South Vietnam seemed on the edge of collapse that was generally seen as the beginning of a communist takeover of all Southeast Asia, and a direct threat to the stability of Asia and the security of the United States. The president and his advisers were convinced that only firm action would prevent this disaster, and the administration launched Rolling Thunder, a campaign to bomb selected military targets in North Vietnam. The U.S. had entered gradually into this war, and suddenly there was no way out. There seemed no realistic hope for a negotiated settlement.

By the summer of 1965, enemy forces threatened to cut South Vietnam in half. The only hope of avoiding a communist victory, the president was told, was to send in U.S. ground forces. In the months ahead, American troops were sent to Vietnam, until by 1968, half a million Americans faced the enemy in South Vietnam’s jungles and highlands. Haunted by the accelerating cost of the war in suffering and national unity, but convinced that capitulation would lead to disaster, the president searched desperately for a viable way out. He could find none.

“I do not find it easy to send the flower of our youth, our finest young men, into battle. I have spoken to you today of the divisions and the forces and the battalions and the units, but I know them all, every one. I have seen them in a thousand streets, of a hundred towns, in every state in this union—working and laughing and building, and filled with hope and life. I think I know, too, how their mothers weep and how their families sorrow.”

—Lyndon Baines Johnson, July 28, 1965.

Milestones in the Vietnam War:

- SEATO and Vietnam

- Vietnam, early 1960s

- Gulf of Tonkin

- Rolling Thunder

- The War That Broke America’s Will

- Tet Offensive

- Attempts for Peace

- LBJ looking back

Cities Under Siege

“When violence breaks out,” the president would say later, “my instinct is to ask: What caused it?” Riots erupted in several major cities, including Los Angeles in 1965. Disturbingly aware that the riots—“countless years of suppressed anger exploding outward”—paradoxically coincided with his administration’s civil rights bills, Johnson addressed both sides of the paradox. He saw the frustrating gap between “hopes aroused” and the fulfillment of those hopes, but condemned it as a reason for violence: “A man with a Molotov cocktail in his hands is not fighting for civil rights.”

“Nineteen sixty-eight,” President Johnson wrote after leaving office, “was one of the most agonizing years any president ever spent in the White House. I sometimes felt that I was living in a continuous nightmare.” Dramatic and frightening manifestations of that nightmare were the riots in more than forty American cities in April, following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Although the most extensive, these riots were in fact only the latest to erupt in black urban ghettos during the years of the administration.

March 31, 1968: The Nation Is Stunned

“What weighs heaviest on Lyndon’s mind,” Lady Bird Johnson recorded in her diary, “is: Can he unite the country?... His mind is lashed to the inescapable problem of ‘How and when do I face up to running again or getting out?’”

For over a year, the president had been moving toward a decision not to seek a second term, primarily because he worried that his health would not survive it. Now, concern over the divisions within the nation reinforced his decision. In a speech to the nation on March 31, the president announced that he was de-escalating the conflict by halting most air and naval actions against North Vietnam.

Then, to remove the war from the political climate, he removed himself from political life with words that stunned the nation and the world: “I shall not seek—and will not accept—the nomination of my party for another term as your president.” The president’s speech electrified the nation, and appeared to change the course of the war. Within three days, the North Vietnamese signaled their willingness to negotiate.

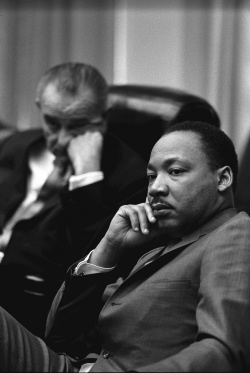

Martin Luther King, Jr. (January 15, 1929 - April 4, 1968)

Martin Luther King, Jr., a Baptist minister and civil rights leader, combined the principles of Christianity and the tactics of Gandhi in his crusade against racial segregation. His use of passive resistance and civil disobedience carried the civil rights movement from the Montgomery, Alabama, bus system to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

On April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated on the balcony just outside his room at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. After King’s assassination, the president met with African-American leaders, seeking and getting their help in trying to restore calm in the nation’s cities. However riots in more than forty American cities in April followed in the wake of the assassination. President Johnson also proposed and persuaded Congress to enact the third major civil rights bill of his administration, an Open Housing Act that prevented discrimination in the sale and rental of homes.

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925 - June 6, 1968)

Robert Kennedy’s presidential candidacy in 1968 inspired enthusiasm across the nation, especially among the young and the disenfranchised. His presidential campaign lasted only two months, but during that short period he touched a generation. As he was leaving the hotel after delivering a speech celebrating his victory in the California Democratic primary, Robert Kennedy was shot on June 6, 1968 in Los Angeles.

Although Johnson’s relationship with Robert Kennedy, unlike that with President Kennedy, had often been stormy, there was a meeting of reconciliation between the two men shortly before the senator’s death. Proclaiming a day of national mourning, the president called his old antagonist “a good and faithful servant of the people,” struck down “in the full vigor of his promise.”

The Administration Winds Down

The final year of the administration—the “nightmare year”—was marked by tragedy and violence. But through it all, the move toward a Great Society continued. A list of 207 “Landmark Laws of the Lyndon B. Johnson Administration,” prepared by the Cabinet, cited 56 of them—including the third major Civil Rights bill, and measures to protect the consumer, preserve the Redwoods, and add public lands and parks for the people’s enjoyment—as having been enacted in this tumultuous year alone.

In the final months, the president met with the two candidates vying to replace him; Vice President Hubert Humphrey and the ultimately victorious Richard Nixon.

At his final State of the Union message, Johnson told the legislators, for reasons that are partly sentimental: “For thirty-eight years I have known these halls, and I have known most of the men who walked them. I know the questions that you face. I know the conflicts that you endure. I know the ideals that you seek to serve. … I hope it may be said, a hundred years from now, that by working together we helped to make our country more just for all of its people. That is what I hope. But I believe that at least it will be said that we tried.”

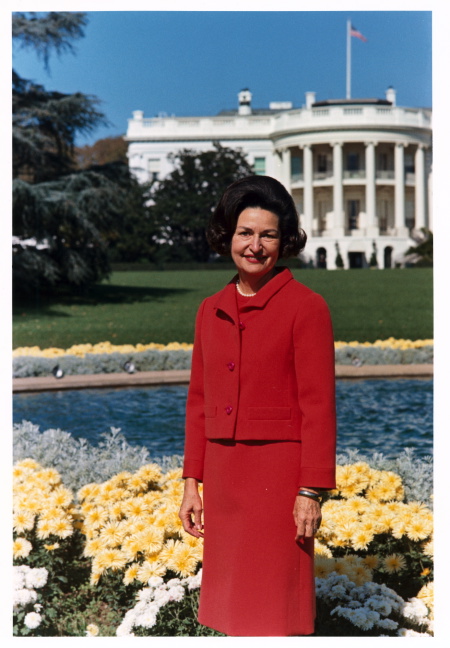

Lady Bird Johnson

Thrust by tragedy into the glare of public attention, Lady Bird Johnson said, “I feel as if I am suddenly on stage for a role I never rehearsed.” Asked what image she hoped to project, she responded: “My image will emerge in actions, not words.”

Early in the administration she served as an interpreter of the Great Society, criss-crossing the country into homes and one-room schoolhouses in poor regions to dramatize the “flesh and blood behind the statistics” of the president’s programs. She was the first national chairman of Head Start, which she hoped would “save a generation of children.”

The image that was her particular and unique identification was tied to the term “Beautification.” She formed a movement to transform the national capital with flowers and trees and grass. She encouraged citizens in every community to spruce up their neighborhoods.

She was the moving force behind the Highway Beautification Act, whose purpose was to remove billboards and junkyards that obscured the countryside. She visited national parks to remind her countrymen of the natural splendors of their native land. With her husband, she brought the large issue of the endangered environment to the nation’s attention.